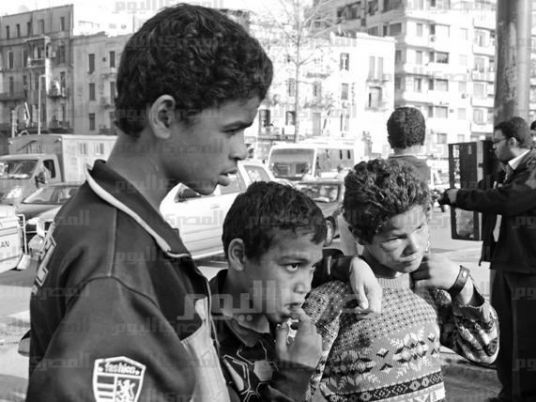

A lot of people have been asking me what the hardest moment has been in my work with street children. I am flooded with choices.

My mind quickly scans the children, and I try to decide which story to tell. In a matter of seconds, I go through the ones who have moved me the most.

Moved me, not so much because of the pain and horror a child has gone through, but because, as part of “mainstream society,” I have either been blind to, oblivious of, or not quite sure about that horror, and so I ignore it.

Was it Maya who tugged at the cords of my heart the most? Maya is a great example of our failure as a society on many levels.

No one was there to notice her familial situation after her parents divorced when she was three years old. For the following three years, no one found out that her stepmother drew an imaginary circle that she had to stay inside — to sleep, play, eat, drink, wee and soil herself.

When she reached six, Maya was allowed out of the circle to become the house maid. She accidently burned the rice and as punishment a metal garlic crusher was thrown at her head. People saw her run to the local coffee shop to find refuge, with blood streaming down her face.

Her father, high on drugs, took her to the roof where he stripped her naked, tied and beat her for upsetting her stepmother. No one could get involved because we are a closed society —what business is it of mine or yours to interfere?

Was it her family?

Oftentimes, people make fun of Egyptians, saying that if someone lost their nose, they could be sure to find it in someone else’s business. But this is not true when it comes to children.

There is a sense of ownership that parents have over their children that has not been sufficiently challenged.

Maya’s story is not an extreme example when it comes to her father. Her stepmother is sadistic, no doubt. But her father?

Maya and her family come from a society where the saying “break a girl’s rib and she will grow 24” is common — a father beating his daughter is often seen as a form of discipline that will do her more good than harm. Maya suffers because she grew up in a society where it’s more honorable for a father to see his child on the street than in an institution.

Maya is not protected by law, as the law states no one can report familial abuse except someone within the family; she is not protected by the social care system, as this system won’t accept her into alternative care without her father’s signature.

Was it society?

Did Maya’s story hurt my conscience the most because when she ran away to the streets, getting onto a train to another city where she knew no one, she was raped by four adult men six days later? Was it because I did not hear of the story, campaign outside the local police station until someone, somewhere, was held responsible for the mental and emotional scars that this resilient, but still fragile little girl had been subject to?

Was it the street?

Or was it the fact that Maya spent three years in an adult prison when she was 13 years old that angers me the most? Having tried for more than two years to get herself into a shelter that couldn’t accept her without her father’s signature, Maya returned to her street family, who told her they would only accept her if she gave herself up for a mugging that they had committed.

The police accepted her confession with no thorough investigation, and she spent three years in the most high-profile adult women’s prison in Egypt.

Was it the police?

Is it her continued bad luck that makes me often wake up in my sleep, crying? Maya married a man who, in her own words, “made me miss my stepmother and remember all the pain my father inflicted upon me like tickles.” The only happy thing about this story was that her husband was put in jail for 15 years for a drug related crime two days after Maya fell pregnant.

Was it her husband?

Or is it that I held Maya’s daughter Samar for two hours, rocking her after her mother had thrown her across the room, crippling her 1-year-old body from the physical abuse. Was it because I couldn’t blame Maya, because I couldn’t protect Samar, or because Maya was inside cutting herself, trying to get rid of what she told me later was her guilt for what she did to her daughter?

Was it her daughter?

By the time I go through just one story in my head, the conversation has already changed. We’re now talking about the Coptic 10-year-old boys being arrested, whether female genital mutilation is really that bad and what age a girl should get married.

These are the topics people are still discussing after a revolution.

But street kids? Street kids, the ones running around burning buildings and throwing Molotovs?

When did society let the street kids down?

Nelly Ali is a human geographer doing her PhD at Birkbeck College, University of London. She works with street girls and young street mothers in Cairo. She can be reached at twitter.com/nellyali